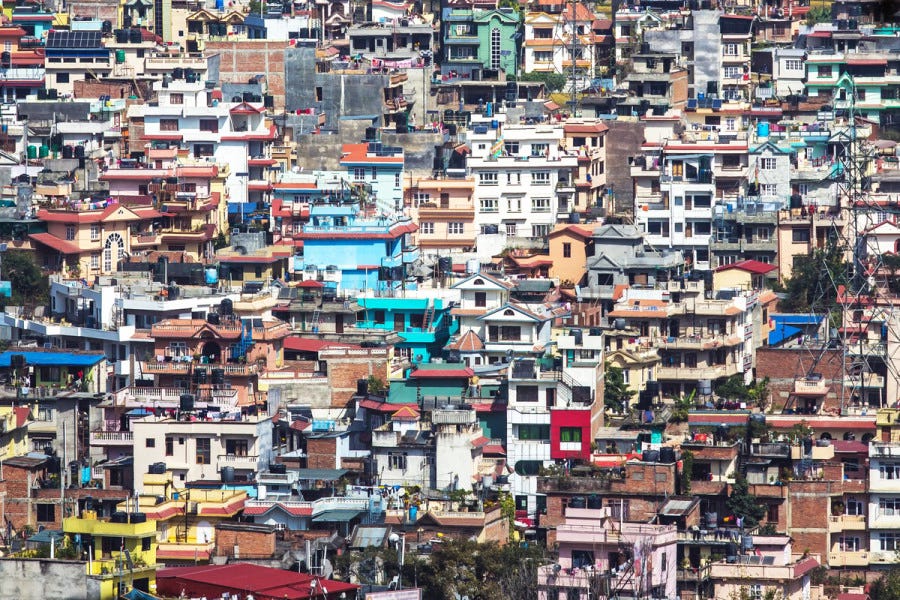

Image: Shutterstock

In Kathmandu a civil servant can gaze wistfully at a modest flat and calculate that, with luck and frugality, it could be his by retirement. At some NPR 8.5m ($62,500), a 185-square-metre apartment in Hatiban now costs the equivalent of two decades’ salary for the average bureaucrat. For a plot in Lalitpur, the same official would need to save for 37 years. In a country where growth is slow and regulation slower, real estate appears to operate under different economic laws. Chief amongst them: up, always up.

Property prices in the Kathmandu Valley are inflating at a rate that would make even the most bullish markets blush. Values are rising by 27.7% a year, by some estimates, doubling roughly every three and a half years, whereas wages inch up by a meagre 7.45%. Land in Bhaktapur has appreciated by an eye-watering 7,000% over two decades. A 33-square-metre plot near Darbar Marg sold for NPR 90m in 2022, making it, square foot for square foot, dearer than parts of Manhattan. Kathmandu, by the numbers, looks less like a capital city and more like a property Ponzi scheme with Himalayan views.

That paradox—sky-high prices in a low-income economy—is underpinned by a potent mix of aspiration, speculation and inertia. Migration from rural districts continues apace: nearly half of Bagmati Province’s population are migrants, lured to Kathmandu by jobs, schools or, sometimes, just the electricity. Supply, constrained by archaic laws and official apathy, has failed to keep pace. And the capital, in more ways than one, has become the nation’s vault.

Remittances have further supercharged this boom. Nepal’s diaspora now sends home $9–10bn a year, most of it bypassing banks and equity markets to find refuge in the comforting tangibility of brick and mud. With little faith in pensions or stocks, many families treat land as their retirement plan. One plot, bought; one son, abroad; one future, secured.

But it is not merely love for land that keeps prices high. It is the elaborate edifice of dysfunction that props it up. Banks lend heavily against land: north of 10% of total lending goes into property, with over 15% of overdrafts similarly tethered. Loans meant for agriculture are routinely funnelled into land purchases. Politicians and contractors, rarely fond of transparency, have piled in too. Former governor of Nepal’s central bank reportedly owns multiple properties, even as the NRB warns of a bubble. In a country where public infrastructure is priced not by cement but by the value of land expropriated, the incentive to inflate land valuations is systemic.

The consequences are manifold. Housing is unaffordable for most, and inaccessible for many. Capital, which might have gone into factories or farms, sits idle under floor tiles. Inequality grows, as the landless subsidise the rentier class. Informality flourishes: transactions are under-declared, taxes evaded, land holdings fragmented illegally. A third of Nepalis no longer live where they were born, yet only a handful can afford to buy where they now reside.

Reforms have been mooted, and then politely ignored. The Supreme Court banned land fragmentation in 2021; 500,000 new titles were issued the same year. Proposals to limit land as collateral, raise transaction taxes or implement inheritance levies have found few takers in Parliament, where, unsurprisingly, many MPs double as landlords.

International comparisons confer little solace. In cities like Seoul or Singapore, where land is equally scarce, prices are kept in check through rigorous planning, public housing and punitive taxes on speculation. Kathmandu, by contrast, treats urban planning as an optional exercise and land tax as a polite suggestion. The fallout is a capital choked by sprawl, where roads lag behind realtors and drainage systems follow deeds.

The bubble for now, if it is one, shows few signs of bursting. Demand persists, supply stutters, government incentives tilt decisively towards inaction. Policymakers may fret in private, but in public they pose with ribbon-cuttings on overpriced infrastructure. Land, after all, makes a pliable scapegoat and an excellent investment.

I can’t quit you baby

Will Kathmandu ever become affordable? Only if the country confronts its political capture, reorients credit towards productivity and dares to imagine value can transcends soil. Until then Nepalis will continue to bank on land not because it is wise, but because it is familiar and because in Nepal land never dies even if the economy around it struggles to be born. ■